(Photo by Alari Tammsalu via Pexels)

By Stephen Beech

Leprosy didn't prevent rich medieval families from being buried in the most prestigious graves, reveals new research.

Wealthy Danes showed off their affluence even in death by being laid to rest "closer to God" in the most expensive plots nearest to churches, according to the findings.

Lepers are often portrayed as being socially stigmatized in the Middle Ages.

But the new study of inequality in medieval graves also showed that stigmatized illnesses - such as leprosy - didn’t bar people from socially prestigious burials.

An international team of archaeologists used graveyards in Denmark to investigate social exclusion based on illness.

They looked at whether people with leprosy - a highly stigmatized disease culturally associated with sin - or tuberculosis (TB) were kept out of the higher-status areas.

(Photo by JP Nunes via Pexels)

Unexpectedly, they found that people who were ill with stigmatized diseases were buried just as prominently as their peers.

Study lead author Dr. Saige Kelmelis, of the University of South Dakota, said: “When we started this work, I was immediately reminded of the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, specifically the scene with the plague cart,”

“I think this image depicts our ideas of how people in the past — and in some cases today — respond to debilitating diseases.

"However, our study reveals that medieval communities were variable in their responses and in their make-up.

"For several communities, those who were sick were buried alongside their neighbours and given the same treatment as anyone else.”

Dr. Kelmelis along with researchers from the University of Southern Denmark examined 939 adult skeletons from five Danish medieval cemeteries - three urban and two rural - to capture possible differences between towns and the countryside.

The research team explained that higher population density makes it easier for both leprosy and TB to be transmitted, and unhealthy conditions traditionally associated with medieval towns increase vulnerability to both diseases.

But the two diseases impacted patients’ lives differently.

Wikimedia Commons

Leprosy patients’ facial lesions would have marked them out as different, unlike the less-specific symptoms of tuberculosis.

Dr. Kelmelis said: “Tuberculosis is one of those chronic infections that people can live with for a very long time without symptoms.

“Also, tuberculosis is not as visibly disabling as leprosy, and in a time when the cause of infection and route of transmission were unknown, tuberculosis patients were likely not met with the same stigmatisation as the more obvious leprosy patients.

"Perhaps medieval folks were so busy dealing with one disease that the other was just the cherry on top of the disease sundae.”

The research team assessed disease status for each skeleton, as well as how long each person had lived.

Leprosy leaves behind evidence of facial lesions and damage to the hands and feet caused by secondary infections, while TB affects the joints and bones near the lungs.

Scientists then mapped out the cemeteries, looking for any demarcations that would indicate status differences, such as burials within religious buildings.

They plotted each skeleton on maps, looking for differences between higher- and lower-status areas.

Dr. Kelmelis said: “There is documentation of individuals being able to pay a fee to have a more privileged place of burial.

“In life, these folks - benefactors, knights, and clergy - were also likely able to use their wealth to secure closer proximity to divinity, such as having a pew closer to the front of the church.”

The findings, published in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, showed no overall link between disease and burial status.

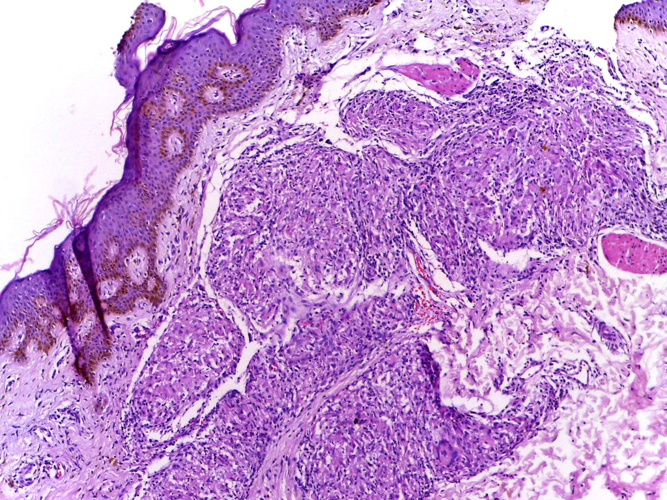

Section of skin showing epithelioid granulomas in the dermis and reduction in the number of appendages. (Department of Pathology, Calicut Medical College via Wikimedia Commons)

Only at the urban cemetery of Ribe were there any differences that correlated with health.

Around a third of people buried in the lower-status cemetery had TB, compared to 12% of the people buried in the monastery or the church.

As people with leprosy or TB were not excluded from higher-status areas, the research team believe that reflected different levels of exposure to TB, not stigma.

All the cemeteries studied contained many TB patients - especially the urban cemetery of Drotten, where nearly half the burials were in high-status areas and 51% had TB.

The researchers pointed out that people who could afford prestigious graves could also have paid for better living conditions, which helped them survive TB long enough for the disease to mark their bones.

The team say their findings suggest that medieval people were less likely to exclude the visibly sick from society than stereotypes indicate.

But they said more excavations are needed to get a more complete picture.

Dr. Kelmelis added: “Individuals may have been carrying the bacteria but died before it could show up in the skeleton.

“Unless we can include genomic methods, we may not know the full extent of how these diseases affected past communities.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.